Architectural models are often shoved into back rooms or even relegated to the scrap heap, given that architects don’t necessarily want to show off their rough drafts.

But, like outtakes from a classic film or early versions of a great novel, the models can be more interesting to students and architecture fans than the final product, since they offer a window onto the creative process. In an age of computer renderings, they also give a vivid sense of how a building looks and feels.

So at age 72, the architect Richard Meier has decided to invite the outside world in, giving visitors a chance to sample an array of models from projects spanning his 40-year career. Stored in a bare-bones 3,600-square-foot studio in Long Island City, Queens, the collection ranges from Mr. Meier’s residential houses of the 1960’s to early versions of his J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles in 1997.

It’s not an elegant space: the lighting is not particularly striking, and the floor is scratched from moving the models this way and that. But Mr. Meier is eager to welcome visitors.

“I realized I should really have people in because it just sits here,” the architect said in a recent interview at the studio. “To have all this and have no one see it is kind of crazy.”

The space, which can be seen by appointment only on Fridays, by no means contains the entirety of Mr. Meier’s work; much of it is still kept at his 10th Avenue office in the West 30s in Manhattan. But there is a substantial sampling — about 300 models. “You see I don’t throw a lot away,” he said.

While Mr. Meier has gained broad attention for projects like the 2003 Jubilee Church on the outskirts of Rome, with its soaring white concrete sails, or his recent boxy glass condominiums along the Hudson River in Manhattan, he is perhaps most closely associated with his sprawling hilltop complex for the Getty in the Santa Monica Mountains.

And it is the Getty that dominates Mr. Meier’s Long Island City studio. Until 1996, the models were kept in Los Angeles, but when the museum needed the space, Mr. Meier had them shipped to a warehouse in Queens. “I didn’t want them to get destroyed,” he said. “There is too much work here to discard them.”

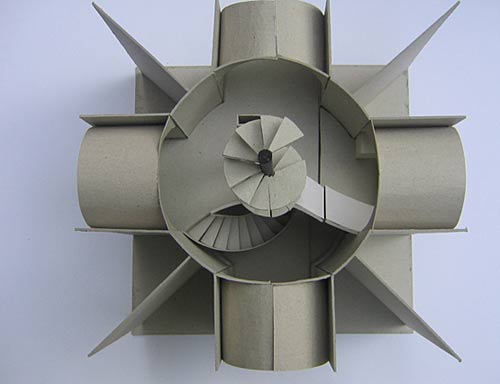

The Getty remains perhaps Mr. Meier’s most ambitious project, with six separate buildings, plazas, an underground parking garage and a tram station on a challengingly steep 110-acre site. Landscaped gardens integrate the structures into the topography.

Immense models of the Getty are on view at the studio — the largest is 18 feet long and 11 feet wide, on wheels and with detachable pieces. “You can get into it more by being able to pull it away and really see into the spaces,” Mr. Meier said. “We had to take the skylight out to get it in here.”

Mounted on the wall is another large model that reflects how the structures were organized along a natural ridge in the hilltop. “You can see the way in which we cut into the earth, as well as building on top of the earth,” Mr. Meier said.

Perhaps most striking is a large-scale gallery mock-up that Mr. Meier had constructed so that people could step inside to experience it — how the sun slanted through the skylight, for example, and whether that natural light landed softly enough on reproduced paintings from the Getty’s collection, pinned to the walls. “We would wheel this into the parking lot and sit in it with curators,” Mr. Meier said.

Over all, the project took 13 years to complete, from 1984 to 1997. When the Getty Center finally opened, Herbert Muschamp, writing in The New York Times, called it “a stupendous new castle of classical beauty.” Some 30,000 people normally visit each week.

Smaller Meier study models focus on specific aspects of the Getty — different versions of skylights, trellises, land contours. You can see how he experimented with the Getty’s auditorium, playing with the seating arrangements and the shape of the ceiling. Shelves hold miniature versions of Mr. Meier’s boxy, modern furniture designs for the Getty — single chairs, double chairs, triple benches.

Among the other buildings represented are Mr. Meier’s first model of the Smith House (1967), a Connecticut residence overlooking Long Island Sound whose private areas are organized on three levels behind an opaque facade with windows. His Hoffman House in East Hampton, N.Y., completed the same year, is a three-dimensional abstraction of interlocking geometries.

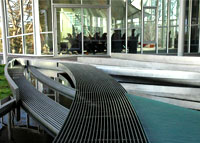

And there is his Royal Dutch Paper Mills headquarters in Hilversum, the Netherlands, from 1992, featuring an interior street illuminated by natural light that enters through each side of a winglike roof.

There are also the projects that never got built. Mr. Meier offers glimpses of a 1981 headquarters for Renault outside Paris, and a “Memorial Square” he designed for the former World Trade Center site in Manhattan in collaboration with Eisenman Architects, Gwathmey Siegel & Associates and Steven Holl Architects. Mr. Meier said he was still fond of the design for the square, defined on the east and north with geometric gridlike buildings made of glass, and referred to it as “a lost opportunity.”

On the studio floor are Mr. Meier’s quirky, hulking sculptures, fashioned from the detritus of various architecture projects. Assemble the castoffs, Mr. Meier said, and “it becomes something else.”

But he hasn’t been making them lately. “I have no more room,” he said.